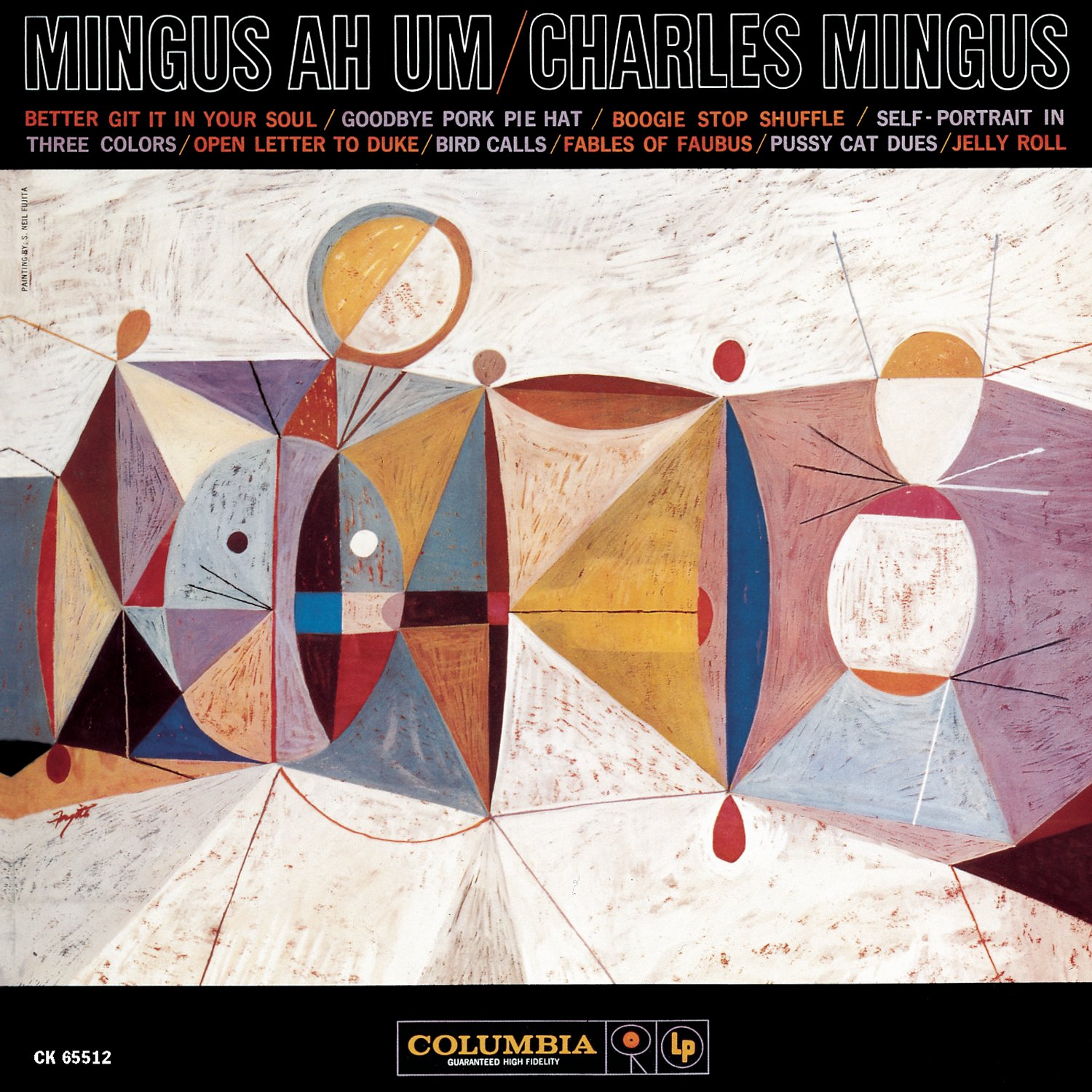

Discussion surrounding the massive and lauded discography of jazz legend Charles Mingus is too often centered around The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, but for good reason. It’s arguably jazz’s most blunt, passionate, and defining work. As one of my favorite online music critics (@Birdmusiclog on Instagram for anyone curious) puts it, it’s “Charles Mingus’s album about how history works.” The Black Saint shows the darkness in America, and channels the dark history of African-Americans into a cry for justice drowned out by saxophone sirens and gunfire drums. However, as the orchestration comes together in the end, a lone horn shrieks like the call of a rooster announcing the rising of the sun that will drown out America’s darkness. If The Black Saint is the winter, it concludes with the promise of a glorious spring. That makes Mingus Ah Um, Charles Mingus’s other masterpiece, the gentle but unpredictable autumn.

Released in October of 1959, Mingus Ah Um plays like fall weather. It can turn from a gentle, relaxing breeze, to a whipping, howling gale in an instant, and Mingus isn’t afraid to place those two sides together in stark contrast. This album starts on the latter conditions with “Better Get Hit In Your Soul,” a foot tapping, hand clapping piece that contains all the energy that made jazz the dance music of choice for decades, while also containing all the instrumental virtuosity you could ask for, with Dannie Richmond’s drum work being particularly of note. “Better Get Hit” is then followed by “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” a slow, soothing, beautiful meditation on mortality.

But Mingus Ah Um contains so much more than the contradiction between chaos and calm. It accomplished what The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady does in a much more intimate and individual way. Many of the song titles contain references to specific people. Songs like

“Open Letter to Duke” and “Jelly Roll” pay homage to other jazz legends and immortalize their names, Mingus’s way of securing their place in history. “Fables of Faubus” alludes to the Arkansan governor who fought the desegregation of schools. Mingus Ah Um is also about “how history works,” it just uses people to paint its portrait rather than society. This album’s smaller and more focused approach is what makes it stand out in Mingus’s discography, and the result of that approach is one of the most emotionally potent and engaging jazz albums of all time.

But when I listen to Mingus Ah Um, I rarely consider the many people, events, and pieces that form this magnificent puzzle. I instead always see a pathway lined with naked trees and carpeted with orange and brown leaves stirring with the breeze, and Charles Mingus never fails to engross me in his wonderful, autumnal world.